Thought for the Day - 17 Sep 2025

Below is the transcript of my Thought for the Day on BBC Radio 4’s Today programme this morning. But you can catch up on my Thought for the Day on BBC Sounds here.

Good morning,

Have you ever considered that… you might be… wrong?

It’s something that occurred to me while listening to this programme yesterday.. Professor Brian Cox was interviewed about his appointment to a new role at the Francis Crick Institute championing the role of science in shaping our world. He explained how scientists provide a great example to the rest of us of being open to being wrong, to having our preconceptions challenged.

Cox quoted 20th century physicist Richard P. Feynam who described science as “a satisfactory philosophy of ignorance”. For Cox, science provides a “flexibility of thought” that means you’re not upset if your worldview turns out to be wrong in some way”.

One of the markers of the polarised age we’re in is a seeming unwillingness to concede we might be wrong. So many of us are uncompromising in our views of the world; we know where we stand on immigrants, or flagwavers. We’re unable to see that these views might be shaped by echo chambers and what we’re being fed by the algorithm. When St Paul said that in this life we “see through a glass darkly”, he was saying that when it comes to divine truths, none of us has the full and objective picture; our view is obscured.

The New Testament has many stories of people getting things wrong and being surprised by their assumptions of who Jesus is versus what they had expected him and the kingdom of God to be like.

Jesus had this habit of making people rethink what they had thought before. You’ve heard it said an eye for an eye, but I say to you turn the other cheek, he said in his Sermon on the Mount.

He said it was servanthood that was the marker of greatness. The disciples thought they would see their enemies defeated but instead witnessed Christ’s humiliating and torturous crucifixion.

We all of course have strongly-held convictions. And there are some beliefs I hold, that I hope really are right, rather than just my subjective opinions: the equality of every human being no matter their gender, no matter their race or religion; that human beings are capable of thinking beyond their own self-interest to the interests of all, that it’s possible to love your neighbour as yourself, that God has no favourites.

Nevertheless being wrong is part of being human. Christian author and apologist GK Chesterton put it like this: “The answer to the question, ‘What is wrong?’ is or should be, ‘I am wrong., he said, “Until a man can give that answer, his idealism is only a hobby.”

Maybe what the world needs is more “flexibility of thought”, more compromise, more of the humility required to build our common life together. Maybe being proved wrong can’t fix all our problems, but maybe it can be a start.

Women Talking: Where to find me at Greenbelt Festival

Greenbelt is one of the highlights of my year. I haven’t missed one since I *think* 2011, and am privileged to have increased my involvement with the festival over the years - from talks team planning to being on the board of trustees, where I am currently vice-chair.

But without doubt one of my favourite things to do is host conversations and panels. Over the years, I’ve interviewed or spoken alongside people including Dr Rowan Williams, Caroline Lucas, Paul Mason, Emma Dabiri, Reni Eddo-Lodge, Vicky Beeching, Rachel Mann, Paula Gooder, Jendella Benson, Sekai Makoni, Andrew Copson, and more!

This year the festival takes place Thursday, 21 August - Sunday, 24 August, at Boughton House in Kettering, and I’m particularly excited about the conversations I’m taking part in with three amazing women. Details below of who these women are, and where and when you can find us at Greenbelt.

Adjoa Andoh

Adjoa is an actor, writer, director, with a career spanning four decades. As an actor she is currently best known for playing Lady Danbury in Bridgerton and in its prequel Queen Charlotte: A Bridgerton story, for which she is a three-time nominee at the NAACP Awards.

She’s also had lead roles at the National Theatre, Royal Shakespeare Company, Royal Court Theatre, Young Vic, The Kiln, and in 2019, she conceived, co-directed and played the lead in Richard II at Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre in the UK’s first all women-of-colour production. 2023 saw Adjoa direct, co- produce and play the lead in a new theatre production of William Shakespeare’s Richard lll for Liverpool Playhouse and The Rose Theatre Kingston – also now a film. I’ll be interviewing her, and talking all things arts, race, womanhood and faith.

Lady Danbury at Boughton House - Pagoda - Saturday, 11am (More details here)

Liz Carr

Liz is best known for her role as formidable forensic examiner, Clarissa Mullery, in Silent Witness (BBC One). Other TV credits include Good Omens (Amazon), Les Miserables (BBC One), Independence Day (BBC), and This Is Going To Hurt (BBC). I’m a fan of Silent Witness, but have become even more of a fan of Liz since she became a vocal advocate against assisted dying. Ahead of the passing of the Leadbeter Bill earlier this year, Liz hosted BBC documentary – Better Off Dead? which explores the repercussions of assisted suicide, and why she believes it shouldn’t be legalised in the UK. Catch us in conversation:

Vocal Witness - Pagoda - Saturday, 2pm (More details here)

Beth Allison Barr

I am so unbelievably excited that Professor Barr will be coming all the way from the US to be in conversation with me about our two books. Hers The Making of Biblical Womanhood and Becoming the Pastor’s Wife, and mine Unmaking Mary: Shattering the Myth of Perfect Motherhood. Professor Barr’s book was one of those that shaped mine, and I was delighted when she agreed to write the foreword to Unmaking Mary. We’ll have lots to discuss at Greenbelt: from the Virgin Mary to tradwives on Instagram, we’ll explore how society’s interpretations of the Bible have distorted how women are seen.

Making and Unmaking - Pagoda - Saturday, 5pm

But wait, there’s more…

As well as these conversations with women, I’ll be taking part in two other panels:

Hope in the Dating: Finding love and connection in a disconnected world

As we explore whether technology has made it easier or harder to form genuine connections, are we at a cultural turning point in how we approach dating and relationships? How can we keep honesty and authenticity at the heart of our interactions? I’ll be joining Beth Chan, Lamorna Ash, Seth Pinnock and Vicky Walker (chair) in what promises to be a fascinating conversation.

Friday - Pagoda - 8pm

And finally…

Church: Do you still go?

Quiet revival or quiet denial? Is big best or is small beautiful? What keeps you going or sends you running? Can we belong without believing - or vice versa? Have you given up or have you found another way? These are just some of the questions Martin Wroe will be putting to me, Lamorna Ash, Jayne Manfredi, Andrew Rumsey and John Philip Newell.

Saturday - Pagoda - 8pm

It’s going to be a busy one… but I wouldn’t have it any other way?

Still time to get your tickets to Greenbelt. Come for the whole weekend, come for the day, or tune in to the No Fly Zone online events from home.

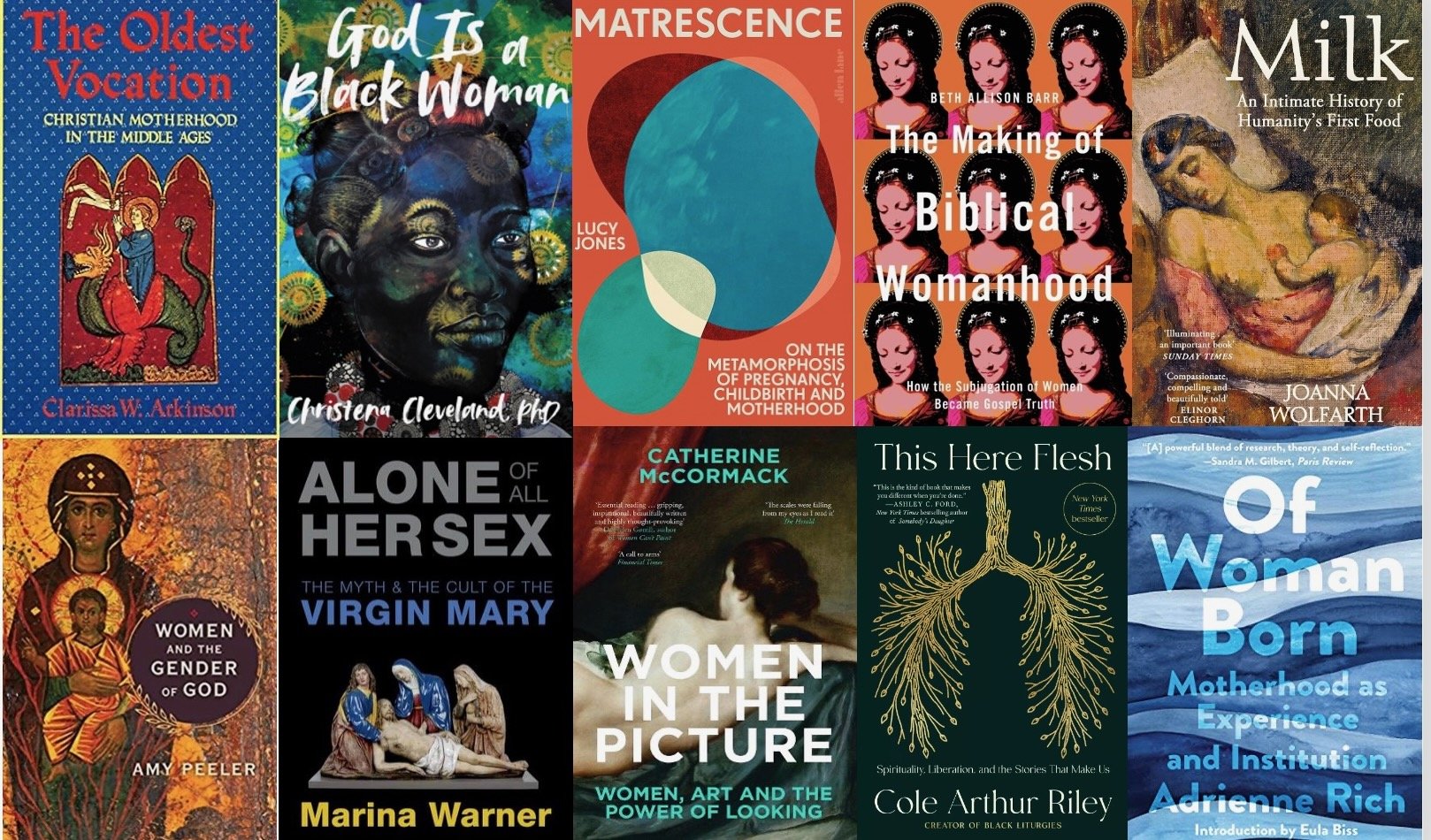

10 books by women that helped me write Unmaking Mary

This is an exciting week. Today is World Book Day, and tomorrow is International Women’s Day. Today also marks exactly ONE WEEK until my new book Unmaking Mary: Shattering the Myth of Perfect Motherhood is launched. (If you’d like to have it in your hands on publication day, then I’d love you to consider pre-ordering it!)

During my research, I read so many wonderful books by women. I went down rabbit holes of academic papers and books in which women had held the pen, detailing their own revelations and frustrations about the maternal experience. Women theologians who had explored the nature of God and the nature of Mary’s motherhood. Historians who had painstakingly researched the truth about the constructions of womanhood and motherhood both in and outside the Church.

To mark World Book Day, International Women’s Day, and the countdown to my new book, I’m sharing some of the books by women that shaped Unmaking Mary.

Of Woman Born – by Adrienne Rich

Almost every book about motherhood I read that was written in the past 30 years or so referenced Of Woman Born by feminist poet and writer Adrienne Rich. The 1976 book examines the institution of motherhood and its historical, social, and political implications. Rich distinguishes between the experience of motherhood as a personal, intimate reality and the institution of motherhood as a system that has been shaped by patriarchal control. She critiques how women’s reproductive and nurturing roles have been used to oppress them while also exploring the potential for motherhood to be a source of strength and autonomy. Blending personal reflection, historical analysis, and feminist theory, Rich challenges traditional narratives, urging women to reclaim agency over their bodies, choices, and identities. Rich’s description of ‘the institution of motherhood’ became a framing for me to describe the ways Mary, the mother of Jesus, has been constructed as an embodiment of this ‘institution’.

This Here Flesh – by Cole Arthur Riley

I love this book so much, and was proud to host a conversation with Cole online for the UK launch of the book a few years ago. It is just the most beautifully written exploration of bodies and spirituality. For me, motherhood gave me a new insight into my ‘embodied-ness’. Pregnancy and childbirth, and the subsequent physicality of the early years of looking after another person, made me feel more like a ‘body’ than I had felt my whole life. I explore these themes in the chapter in Unmaking Mary called This Is My Body Broken for You. Written by Cole Arthur Riley, the creator of Black Liturgies, This Here Flesh delves into themes such as dignity, belonging, lament, and joy, drawing from her own experiences and the stories of her ancestors. Here Riley challenges oppressive structures while affirming the sacredness of Black embodiment and existence. The book serves as both a spiritual meditation and a call to embrace the fullness of one’s humanity, offering readers a profound and intimate journey toward healing and justice. I was so delighted to receive an endorsement from Cole for Unmaking Mary, which she described as “vital reading for all who were once born”.

Matrescence – by Lucy Jones

I am evangelical about this book, and refer to it time and time again. Matrescence: On the Metamorphosis of Pregnancy, Childbirth and Motherhood (2023) by Lucy Jones is a deeply personal and scientific exploration of the profound transformation that occurs when a person becomes a mother. Drawing on neuroscience, anthropology, psychology, and her own experiences, Jones examines how motherhood reshapes the body, mind, and identity in ways often overlooked by society. I was also particularly fascinated by her exploration of motherhood as an existential and spiritual turning point – something that is rarely talked about. She challenges the cultural narrative that views motherhood as solely instinctual or self-sacrificial, instead presenting it as a complex, evolving process similar to adolescence. It is a beautifully written and rigorously-researched book, and advocates for greater recognition and support for this life-changing transition. We’re looking forward to working closely with Lucy Jones in an upcoming project on motherhood, and I was delighted to interview her for our new four-part documentary podcast Motherhood vs the Machine (also being launched on 13 March).

The Oldest Vocation – by Clarissa W. Atkinson

The Oldest Vocation: Christian Motherhood in the Middle Ages (1991) by Clarissa W. Atkinson explores the historical and religious construction of motherhood in medieval Christian thought. Atkinson traces how motherhood was idealised, both biologically and spiritually, as a sacred vocation shaped by theological, social, and cultural forces. She examines how the Virgin Mary became the ultimate maternal model, influencing expectations of women’s roles in family and society. The book also highlights contradictions within these ideals, revealing the tension between reverence for motherhood and the restrictive norms imposed on women. Through historical analysis, Atkinson uncovers how medieval Christian views on motherhood continue to influence contemporary gender roles and expectations.

Milk – by Joanna Wolfarth

Milk: An Intimate History of Breastfeeding (2023) by Joanna Wolfarth is a cultural and historical exploration of breastfeeding, motherhood, and the societal forces that shape our understanding of both. Blending personal narrative with research spanning anthropology, art, history, and science, Wolfarth examines how milk has been revered, politicized, and commodified across different cultures and time periods. She challenges idealized notions of motherhood and the pressure placed on women’s bodies, highlighting the complexities and struggles many face with breastfeeding. Through this deeply personal yet widely researched account, Milk sheds light on the intersection of biology, culture, and gender, offering a fresh perspective on one of humanity’s most fundamental experiences. I’m excited to be doing an event themed around Unmaking Mary with Joanna at the National Gallery on 23 May (more information here). We’ll also be joined by the author of the next book I want to celebrate…

Women in the Picture - by Catherine McCormack

Women in the Picture: Women, Art and the Power of Looking by Catherine McCormack explores how women have been portrayed in Western art history and the impact of these representations on cultural perceptions of femininity. McCormack critically examines the ways in which male artists have often objectified, idealised, or diminished women in visual culture, reinforcing gender stereotypes. She contrasts these traditional depictions with alternative narratives that reclaim women's agency in art. Through analysis of classical paintings, contemporary media, and feminist theory, Women in the Picture challenges the viewer to see beyond the dominant male gaze and reconsider how women’s stories are told through imagery.

Alone of All Her Sex - by Marina Warner

Alone of All Her Sex: The Myth and the Cult of the Virgin Mary (1976) by Marina Warner is a groundbreaking exploration of the Virgin Mary’s role in Christian tradition and Western culture. Warner examines how Mary has been venerated throughout history, analyzing the ways in which her image has shaped and reinforced ideals of femininity, purity, and motherhood. She traces the evolution of Marian devotion, from early Christianity to the present, highlighting how the cult of the Virgin has both empowered and restricted women. Through a blend of historical, theological, and feminist analysis, Alone of All Her Sex critiques the ways in which Marian ideology has contributed to limiting women's roles, while also recognizing Mary’s enduring influence as a spiritual and cultural symbol.

Women and the Gender of God - by Amy Peeler

Women and the Gender of God (2022) by Amy Peeler is a theological examination of the gendered language used for God and its implications for women in Christian faith. Peeler, a New Testament scholar, challenges patriarchal interpretations that have historically excluded women from positions of spiritual authority. She argues that while God is often described using masculine terms, the biblical narrative also presents maternal and feminine imagery, offering a more inclusive understanding of the divine. Peeler explores how the incarnation of Jesus, born of a woman without male involvement, highlights the significance of women in God’s redemptive plan. Through scriptural analysis and theological reflection, Women and the Gender of God seeks to affirm the dignity and spiritual authority of women in Christian tradition.

God Is A Black Woman – by Christena Cleveland

God Is a Black Woman (2022) by Christena Cleveland is a powerful exploration of theology, race, and gender, challenging the dominant perception of God as a white male. Cleveland, a social psychologist and theologian, embarks on a deeply personal pilgrimage to dismantle the oppressive religious narratives that have shaped her faith and identity. Drawing on history, spirituality, and her own experiences, she reclaims the sacred image of the Black Madonna, presenting a vision of the divine that is nurturing, liberating, and deeply connected to the experiences of Black women. Through this journey, God Is a Black Woman offers a radical reimagining of faith, inviting readers to break free from white patriarchal theology and embrace a more inclusive, healing spirituality.

The Making of Biblical Womanhood – by Beth Allison Barr

The Making of Biblical Womanhood: How the Subjugation of Women Became Gospel Truth (2021) by Beth Allison Barr is a historical and theological critique of complementarianism—the belief that men and women have distinct, divinely ordained roles in the church and home. As a historian and pastor’s wife, Barr examines how patriarchy was not a biblical mandate but rather a cultural construct reinforced by centuries of church tradition. She traces how women in early Christianity held significant leadership roles, only to have their authority diminished over time. By blending personal narrative with historical scholarship, Barr challenges the notion that female submission is God-ordained, arguing instead that it is a product of human power structures. Ultimately, The Making of Biblical Womanhood calls for a re-examination of gender roles in the church, advocating for women’s full inclusion in Christian ministry. I was absolutely delighted when Beth agreed to write the foreword for Unmaking Mary and even more delighted when I read what she had written. Beth absolutely got what I had been trying to say, and it was so fun chatting over breakfast with her a couple of months back when she was in London.

To pre-order your copy of Unmaking Mary: Shattering the Myth of Perfect Motherhood, and receive it on publication day (13 May), you can pre-order here.

Thought for the Day - 30 July 2024 - Weeping with Southport

The following is the script I delivered on BBC Radio 4’s Today programme on Tuesday, 30 April 2024. You can listen back on BBC Sounds here.

—-

Good morning,

‘Mummy, can children die?’

The words came from my then five-year-old who was sitting at the back of the car as I drove him home from school. I’d long dreaded the question – but I still wasn’t prepared for it. I winced. Yes. And knew in that moment that something of his innocence had been taken away.

Like every mother, I’d wanted not only to keep him safe from physical harm, but also to protect him from the knowledge of heartbreak and pain.

I know that I began to see the world differently when as a child I realised that such a horror was possible. Death is something we must all wrestle with, but the death of a child is a tragic upending of the order of things. Children killed in violent ways by human hands: unthinkable.

That such a horror can happen in a place like Southport, as it did yesterday? Unbearable. The incongruence of the terrible scenes taking place at a Taylor Swift dance party for children at the start of the summer holidays makes it even harder to fathom.

There are no easy answers to why such terrible things take place; no ways to make it better. For the parents of the children that died yesterday in the horrific attack, for those who were injured and will forever be traumatised by what took place, pat answers – religious or otherwise - just won’t do.

There is no word in the English language for a parent whose child has died. Widows and widowers have lost their spouses, orphans have lost their parents. But a parent whose child has died – whether in Southport or Israel or Gaza or Ukraine – it’s too painful for us to even name.

In the Massacre of the Innocents – the children killed by King Herod after the birth of Jesus – the gospel of Matthew alludes to an Old Testament passage that reads:

“A voice is heard in Ramah,

weeping and great mourning,

Rachel weeping for her children

and refusing to be comforted,

because they are no more.”

I’ve long found this passage haunting because it paints a vivid picture of my worst nightmare. For the families in Southport, the pain of losing a child is no longer a nightmare, but a living and waking reality.

In wrestling with such tragedy, the biblical writers present us with images of a God who steps in to our worst days, the pain of our nightmares, and sits in solidarity with those who find themselves in the valley of the shadow of death. And with those who mourn. ‘God is near to the brokenhearted,’ it says in the book of Psalms.

The days of seeking answers about what happened in Southport will come. But now is too soon. The grief is too raw. Maybe today is the day we too hear the cries of those whose hearts are broken. Maybe that’s all we can do.

Photo credit: Photo by khampha phimmachak on Unsplash

Thought for the Day - 16 July 2024

The following is the script from my Thought for the Day on BBC Radio 4’s Today programme on Tuesday, 16 July 2024. You can listen to it on BBC Sounds here:

Good morning,

Soon after the assassination attempt on Donald Trump, commentators were drawing parallels between Saturday’s attack, and that on Ronald Reagan in 1981. Reagan was forever changed by his close encounter with death, and like Trump, believed he had been spared by God.

In big moments, we look to the past to make sense of what’s happening now. The UK election this month seemed twinned in public consciousness with Labour’s 1997 victory. In the run-up, political analysts pointed to similarities then to predict what might happen in 2024.

Academics have described this as historical recurrence – events in history that bear striking similarity: the rise and fall of empires, catastrophic changes in climate, the assassinations of charismatic activists like Gandhi or Martin Luther King.

Sports fans will be familiar with commentary that points backwards, twinning previous wins or defeats with matches happening now.

We describe football coming home, and hark back to that celebrated day in 1966 that still haunts the collective memory of every England football fan. A major win continues to elude the men’s national team, but the idea that history must at some point repeat itself keeps us hoping that this might be the time.

Gareth Southgate’s penalty miss in 1996 foreshadowed Bukayo Saka’s in the Euros final in 2020. It helps to know others before us have faced the same challenges we have. So much of political and footballing commentary meditates on the past.

The gospels often point back to what’s come before, too. The victories and losses and joys and heartbreaks of Old Testament figures are echoed in the lives of those that come after them.

Eve - the first woman - foreshadows Mary, Jesus’s mother. Jesus is referred to as the new Adam.

Humans can’t help but draw patterns – to trace lines from the past to the present. Perhaps it makes us feel less like we’re floating specs of dust in a universe filled with cosmic randomness, and more like we mean something.

Like what we see, experience, read in our newspapers – is connected to something else. Something bigger. It hooks us in to a larger narrative, and helps us find our place.

I’ve always found the words in Ecclesiastes – that there’s nothing new under the sun - a little depressing. But maybe they can provide a sort of comfort instead.

Like someone, somewhere, has the long view of human history and is in control; or like we ourselves have more control if we can predict what’s coming next.

At the very least – in a world that feels increasingly uncertain – maybe it simply helps us feel less alone.

Image: Pierre Bamin for Unsplash

A place called home - Thought for the Day BBC Radio 4

Delivered live on BBC Radio 4’s Today programme on Friday, 3 November 2023. You can listen to the audio here on BBC Sounds.

Good morning,

My husband and I love talking about home improvements: a loft conversion, complete with sparkly en-suite; a kitchen makeover. A garden room. None of these are on the horizon, but we can dream.

This week, as Storm Ciaran raged, I felt grateful simply walking into the hallway of our home. As I shut the door on the howling wind and entered the safety, shelter and sanctuary of our four walls.

This place strewn with children’s toys, a carpet well-trodden with the stuff of life; this place where I have paced up and down trying to get my babies to sleep, where I’ve laughed till I cried with friends round the dinner table. This place called home.

The desire for aesthetic improvements seems insulting in the face of homes flooded during storms because of climate change, or amid the tragic tales of domicide we see in conflicts around the world.

Like 85-year-old Yocheved Lifshitz, the Israeli woman recently released as a hostage taken by Hamas from her kibbutz, after they burned her home during the horror of October 7th. Or the pregnant mum I met in the West Bank a decade ago, sitting with her seven other children in the rubble of their house, hours after it had been demolished by the Israeli defence force.

When sacred buildings – places of worship that have stood for centuries - are destroyed we feel a collective sense of mourning. These great buildings that house the identity and hope of faith groups and communities.

Something stirs in me when I see images of St Paul’s Cathedral standing tall amongst the bombed-out buildings during the Blitz. Representing spiritual as well as physical resilience.

It's never just about bricks and mortar – essential though they are for our wellbeing. Our physical surroundings testify to our spirits, too.

When Jesus says the temple will be rebuilt in three days, his opponents think he’s talking about the structure that took 46 years to build. Instead, he’s referring to his future resurrection; the hope-filled event that will carry a community of billions of followers for 2,000 years.

Recently, I stood looking at the rubble of my own church. We had demolished it deliberately; our old, decrepit building torn down to make space for a new project in the heart of south-east London.

A place for parents and toddlers to spread their wings and find community among other sleep-deprived souls; a place for those in our bustling neighbourhood to get coffee and good food; a place for us to meet to worship God. But also a place with 33 flats above it for homeless young people. A place of safety and shelter. A place for them to call home.

Photo by Pablo Guerroro on Unsplash.

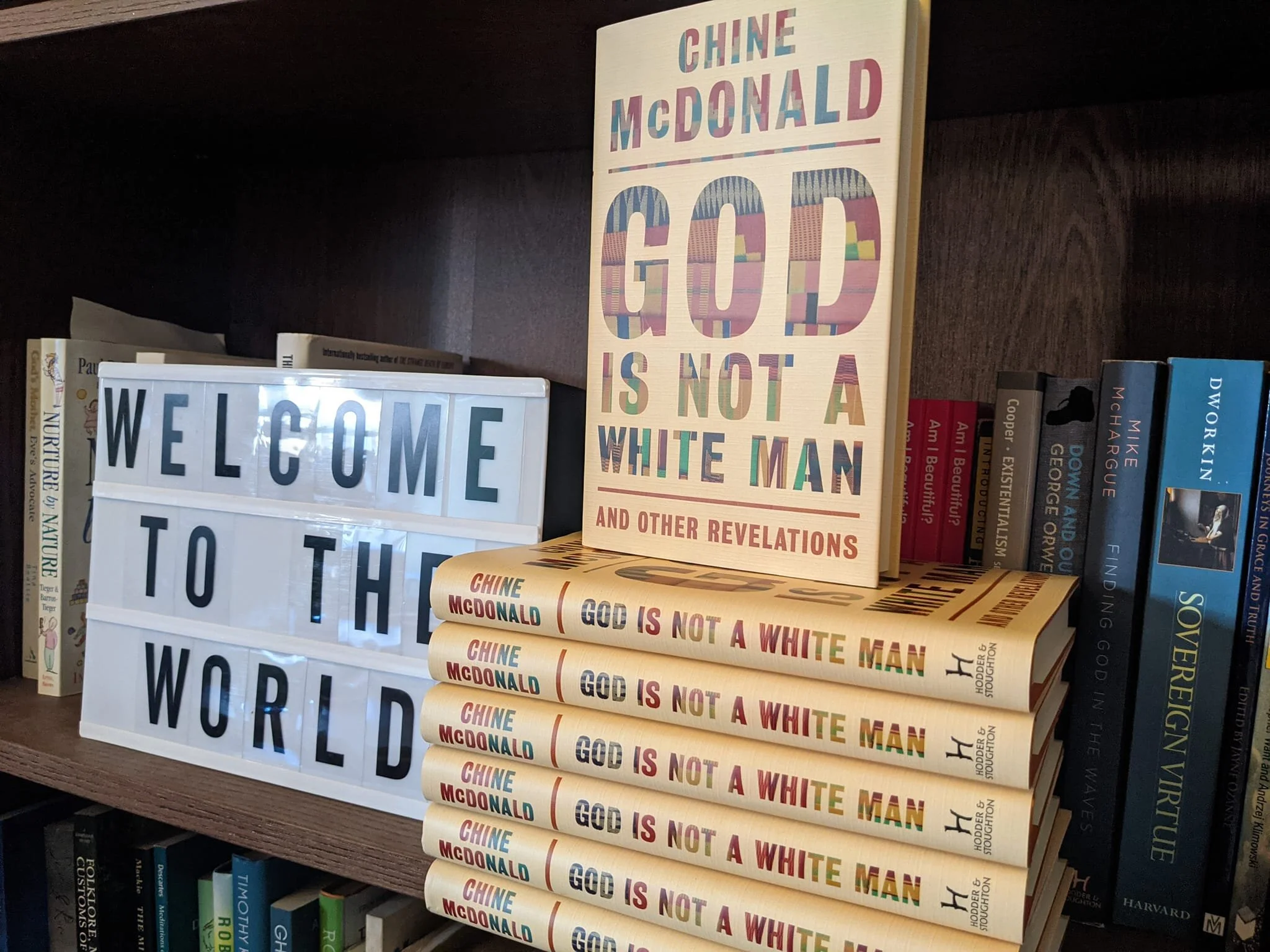

Unmaking Mary: Shattering The Myth of Perfect Motherhood - Coming 2025!

I’m delighted to announce that I’m working on a new book! Details below from my publishers’ press announcement:

Hodder & Stoughton acquires Unmaking Mary: The Myth of Divine Motherhood by Chine McDonald, an honest exploration of the reality of motherhood and the pressures placed by society on 21st century mothers

Hodder & Stoughton is delighted to announce the acquisition of Unmaking Mary: Shattering The Myth of Perfect Motherhood by Chine McDonald. World rights were bought by editorial director Joanna Davey. Hodder & Stoughton will publish Unmaking Mary in hardback in Spring 2025 in the UK and the US.

In Unmaking Mary, Chine McDonald explores how motherhood has been shaped by negative theological and social understandings of what it is to be a woman, in order to change the story about how mothers of all ages are seen and supported by the church.

For two thousand years, the Virgin Mary has been depicted throughout art, literature and culture as symbolising the perfect mother: chaste, beautiful, meek, mild and white. These supposed virtues and symbols have shaped not just Christianity but wider popular culture; and have contributed to harmful views about motherhood and what it is to be a woman. In this part-memoir, part social and theological commentary, Chine McDonald deconstructs the myth of perfect motherhood and shines a light on the darker side of parenting. From birth trauma to post-natal depression, from infertility to the mental load, the motherhood penalty and pressures on women to be it all and have it all, this book aims to liberate motherhood from the chains in which it has been placed, reconstructing a more authentic, grace-filled way forward for the most important job in the world.

Chine McDonald is a writer, author, public theologian and Director of Theos, the religion and society think tank. She was previously Head of Public Engagement at Christian Aid. Chine has two decades of experience in journalism, media and communications across faith, media and international development organisations.

She speaks and writes widely on issues of race, faith and gender, and is the author of God Is Not A White Man: And Other Revelations (Hodder & Stoughton, May 2021). A broadcaster, panel host and media commentator, Chine has written for the Financial Times, The Independent, The Big Issue and The Mirror; she also contributes to various TV and radio programmes, including ‘Thought for the Day’ on BBC Radio 4’s Today programme and BBC1’s Sunday Morning Live. She regularly speaks on and hosts panels, including for the Cheltenham Science Festival and the Cheltenham Literature Festival. She is vice–chair of Greenbelt Festival and a trustee of Christian Aid. Chine studied Theology and Religious Studies at Cambridge University.

Chine McDonald says: “I’m delighted to be working with the Hodder team on another project that is so close to my heart. This book will require me to delve deep into the dark heart of motherhood, critiquing the shiny, saccharine and chaste ideals that leave no room for imperfections. It will not be easy, but I hope and pray through telling the truth about motherhood and what it is to be a woman – warts and all – we’ll uncover the beauty that exists in unexpected places. I believe it’s only in confronting the uncomfortable realities of how motherhood has been shaped by faulty theologies and socio-political constructs that we can all be freed from these constraints. I’m honoured to have been trusted with so many women’s stories as part of this project, and I hope that it might free us all from the shame, chains and judgment that society – and the Church – place on all of us, including those entrusted with the most important job in the world.”

Editorial Director Joanna Davey adds: “I am so pleased that Chine is staying with Hodder Faith for Unmaking Mary, following the success of God Is Not A White Man. Chine’s thoughtful and thought-provoking writing is the kind that brings about change. I’ve no doubt that her meditations on motherhood will have a positive impact for women in the church, and beyond.”

Unmaking Mary will publish in the UK as a hardback at £16.99 in February 2025 and in the US as a hardback at $19.99 in May 2025.

For publicity enquiries, please contact: Rhoda Hardie (Rhoda.hardie.pr@gmail.com)

The Persistent widow and the tireless fight for racial justice

Today (Sunday, 16 October), I delivered the Oxford University sermon at St Mary’s, the University Church:

My foremothers called it Ogu Umunwanyi – The Women’s War. The white men called it the Aba Riots, diminishing the women’s roles in bringing about change and reducing their protest to the frenzied and irrational violence of savages. It took place in November 1929, when thousands of Igbo women – including those from

Umuahia, my ancestral home – protested against the British colonisers who wanted to restrict the role of Igbo women in the governing of their own communities.

The protests of 1929 spread like wildfire, as tens of thousands of women from across 6,000 square miles of southern Nigeria – an area covering around 2 million people – rose up in protest against the British, demanding that ‘all white men should go to their own country’.

Knowing Igbo women as I do, the descriptions of their modes of protest make me smile, not with amusement but with pride. These headstrong, fierce women were just like my mum or grandma or aunties.

They employed traditional methods of protest that only Igbo women could – ‘sitting on’ or ‘making war’ on men whom they believed had been behaving badly. This involved, as anthropologist Judith Van Allen describes:

“Gathering at his compound at a previously agreed time, dancing, singing scurrilous songs that detailed the women’s grievances against him (And often insulted him along the way by calling his manhood into question), banging on his hut with the pestles women used for pounding yams, and, in extreme cases, tearing up his hut

(usually meaning pulling the roof off)… The women would stay at his hut all night and day if necessary, until he repented and promised to mend his ways in the future.”

This month is Black History Month, and as has been so with the injustice experienced by Black people throughout history, the actions of these Igbo women were met with disproportionate force. On two occasions, the British District officers called in the police and the troops, who fired upon the women, killing more than 50 of them and leaving another 50 wounded. This was the first instance of a major anticolonial protest by women in West Africa, and it resulted in the British abolishing the system of warrant chieftains and appointing women to the Native Courts.

In this instance, these African women were able to reclaim the positions of authority they had held before the colonisers came with their regressive notions of the role of women in the functioning of a society.

They got justice through their persistence.

In the Luke 18 passage read earlier, we hear Jesus telling the parable of the persistent widow. A woman who wears down an unjust judge. Who keeps on and keeps on demanding justice until he has no choice but to give it to her, concerned about what she might do to him if she doesn’t get it.

The Greek translation of the text sees the judge use dramatic hyperbole by employing the word hupopiazo - meaning to ‘blacken the eye’. While other translations treat the word as euphemistic for ‘wearing him out’, it’s important we don’t miss the intended sentiment – that the woman may be ready to inflict violence upon the unjust judge, such is the level of her grief.

This is not a woman who lives a privileged life where she can afford to sanitise her anger, to act in a calm and measured way as society might expect of ladies. No, this woman’s life circumstances mean that her anger cannot be contained, her demand for justice not merely relayed in quiet, polite, requests, but the kind of loud protest that hits you right between the eyes; that does not allow you to look away.

Like the Igbo women who employ persistent collective action to achieve the justice they deserve, the widow does not let go until she has it.

I wonder what justice she is seeking. The parable does not spell out the details of the wrong that has been done to her, but the word used for justice here may imply ‘vengeance’. Some wrong has been done to her and she demands it be made right.

The past 400 years of Black history has seen much wrong perpetrated against Black people. It’s been a story marked by violence, oppression and brutality. From the transatlantic slave trade through to the murders of unarmed black men and women by those who were supposed to protect them. The chant that black lives matter is a heart-cry borne out of injustice and pain. Three words that say such tragedies and the rotting flesh of racism that causes them must be rooted out. It’s a cry that says no longer can we dehumanise black men and women. A cry that will not stop until we achieve our full humanity.

Why a widow in the Luke 18 parable? Throughout the Bible we see widows, orphans and immigrants spoken of as the most marginalised in society. By choosing a widow, Jesus is emphasising the fact that in society’s eyes, the odds are stacked against her. Like women of the time, she is seen as a second class citizen just for being a woman. And she has no one to speak for her, which is why she is making demands of the judge alone. It can be implied that this corrupt judge may have been corrupt due to the common practice of being bribed; but this widow does not have the means to bribe him. Instead, it’s her persistence, her petitioning, her prayer that moves the corrupt judge to action.

Hebrew and womanist scholar Dr Wil Gafney describes how the Luke 18 passage demonstrates the persistence and resourcefulness of women to, in womanist parlance, “make a way out of no way; and survive until they can thrive’.

I can think of three black women – not necessarily widows themselves – but those whose persistent campaigning and petitioning in the face of injustice and tragedy has moved mountains. Mina Smallman, Doreen Lawrence and Mamie Till – each mothers of brown-skinned people, loved by God, who were murdered. In the aftermath of their deaths, each mother sought to blacken the eye of the powers that be, demanding justice for their children.

Mina Smallman’s daughters Bibaa Henry and Nicole Smallman were stabbed to death in a park in Brent, London, in June 2020. Mina – who also happened to have been the first female black or minority ethnic archdeacon in the Church of England – maintained that racism was what led to the police not doing enough to find the sisters after they had been reported missing, and racism that led to the horrific sharing of images of the dead sisters’ bodies by police officers at the scene. When Mina Smallman was asked in a Guardian interview earlier this year why she kept on, why she was persistent in her demand for justice, she quoted Emmeline Pankhurst on fighting for women’s suffrage: “You have to make more noise than anybody else,” she said. “You have to make yourself more obtrusive than anybody else, you have to fill all the papers more than anybody else.”

Like the persistent widow, Mina Smallman demands justice and commits to wearing down the powers that be until they give it to her.

In 1955, 14-year-old African American Emmett Till was abducted, tortured and murdered after being wrongly accused of winking at a white woman in a grocery store in Mississippi.

After viewing the brutalized body of her son, his mother Mamie Till-Mobley decided to hold an open casket funeral in the hopes that when the world saw – really saw – the violence committed against her son, that it would wake people out of the slumber of inaction on racial justice. “Let the people see what they did to my boy,” she said. As images of Emmett Till’s broken and mutilated body were featured in magazines, Mamie Till’s prayer was that this injustice could not be ignored and that the authorities would be moved to make change so that nothing like this would ever happen again. We know of course that Emmett Till was not the last black person murdered for the colour of their skin.

I was nine years old living in Eltham in south-east London when teenager Stephen Lawrence was murdered a few streets away from where I lived. His mother Doreen’s name has become synonymous with the fight for racial justice in the UK. She has devoted her life to not just seeing the murders of her son brought to justice, but the police and the authorities held to account for the institutional racism that Stephen’s murder highlighted. She knows she can never give up; that she must be a thorn in their side. She leaves the authorities with no peace.

No justice. No peace.

These three black women, like the persistent widow, demanded justice in the face of tragedy. As black women, they knew full well that justice had not been a friend to black people. In the words of poet and activist Langston Hughes:

That Justice is a blind goddess

Is a thing to which we black are wise

Her bandage hides two festering sores

That once perhaps were eyes.

So what might this parable mean for us today, living in the age of Black Lives Matter – in a world where there seems to be so much injustice?

Ultimately Luke 18 can be seen as a lesson for us to never tire of praying to God for the justice the likes of which we believe we will see in the Kingdom of God. If the corrupt judge can be moved to grant the widow justice, how much more so will a God of justice be moved by our petitions. Your kingdom come, we demand; your will be done, we pray. On earth as it is in heaven.

We recognise however that though we might see glimpses of justice in this, the now and the not yet of the coming of the kingdom of God, God’s ultimate justice will be seen in the coming of God’s kingdom. But for most of us, this feels unsatisfactory.

We join with the psalmist and the Igbo women and the Mina Smallmans and the Doreen Lawrences and Mamie Tills crying out ‘how long, O Lord?’ Crying out for justice in the here and now.

Perhaps you are someone in a position of authority, like the judge in the parable. Or perhaps you have power or are privileged in some way. For the persistent widow and those who have been wronged or oppressed, the constant demand for justice can be exhausting. But it cannot all be on them. At some point, those with power must act in order for justice to happen. Because it’s the right thing to do, not just because we are worn down by the persistent cries of the persecuted.

The Black Church, throughout its persecuted history, has long grasped the reality that the good news of Jesus Christ makes a difference in the spiritual and material realities of our daily lives. It’s not just about where we go when we die.

So may we be persistent in our cry for God’s justice to come in the here and now, to those who are helpless, to those who are unrepresented, to those who are oppressed, who are victims of violence and abuse, to those who are marginalised in so many ways. May we come alongside those who stand alone crying out for justice. As Martin Luther King said, echoing Amos 5:24: “Now is the time for justice to roll down like water and righteousness like a mighty stream. Now is the time.”

Photo by Kalea Morgan on Unsplash

BBC Radio 4: Thought for the Day (That would have been) - 24 February 2022

I was due to present Thought for the Day on BBC Radio 4’s Today programme, but the historic occasion of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine meant the Archbishop of Canterbury Justin Welby was asked to do it instead. Quite rightly. Here’s what I was due to say - perhaps there are some lessons for all of us in how we choose to live our lives in times like these:

Good morning,

“The idea that some lives matter less is the root of all things wrong with the world,” The words of Dr Paul Farmer, a global healthcare advocate, who died this week.

I’ve been struck by the multitude of tributes to both him and 31-year-old British entrepreneur and YouTube star Jamal Edwards, who died on Sunday.

At first glance, these two men’s lives couldn’t have been farther apart – one raised the profile of the UK grime music scene by launching his online music platform SBTV at the age of 15, making room for voices of people from disadvantaged backgrounds. He was later awarded an MBE for his work in this area. The other – a world-renowned American academic who dedicated his life to providing medical treatment to those living in poverty.

And yet both – like the prophets in the Bible - took action when dissatisfied with the status quo, working towards an alternative vision of how the world could be: a place where the voices of the poorest and most disadvantaged could be heard just as loudly as the richest.

This idea is foundational to Catholic liberation theology. Though not without its detractors, its main tenets centre around the poorest as special recipients of God’s grace and how working against oppression is a central part of what it is to be a good Christian, and a good human.

Recent years have made visible the invisible inequalities and oppression of people that can be so easy for many of us to ignore. The hoarding of Covid-19 vaccines by rich nations, while the poorest are left behind; the Black Lives Matter protests laying bare the racial injustice at every level of society; those living in poverty on the frontline of climate change. My understanding of the Christian faith is that the kingdom of God belongs to such as these. The poor. The marginalised. The oppressed. The unexpected.

Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven, Jesus says in Matthew’s Gospel. The poor are blessed not because they possess an inherent piety; but, because as Italian cardinal and priest Raniero Cantalamessa writes, God values what they don’t have: they don’t have self-sufficiency… and they don’t have a presumption of being able to save themselves.

The Christian faith emphasises both the internal condition of being poor in spirit and God’s dissatisfaction with the social condition of poverty and the inequality and injustice that lead to it.

A question for us is what we do about it; whether our lives will be defined by an apathy to the status quo, or whether our legacies will demonstrate a commitment to being the change we want to see in the world – not turning a blind eye to our brothers and sisters living in poverty.

Perhaps as Jamal Edwards’ mother Brenda sang in front of mourners at a vigil for him this week, this is the “greatest love of all”.

BBC RAdio 4: THOUGHT FOR THE DAY - 24 November 2021

Good morning,

On Monday, I attended my latest midwife appointment and was struck again by the care I received. I met both an experienced midwife and a student learning the ropes and was moved almost to tears by their kindness. I’ve found the first few months of this, my second pregnancy, brutal emotionally and physically.

But in that 20-minute appointment, I felt like I mattered – not just as an expectant mother but also as a human being.

While I was there, I thought about the marches all over the UK on Sunday. Thousands of people joined Midwives, doulas, doctors and their families to make a plea for improved working conditions and better funding for maternity care.

The March with Midwives movement began in October after a survey by the Royal College of Midwives found that more than half of them are thinking about leaving the NHS.

There aren’t enough of them as it is and those that remain in the system say they’re stretched and unable to give labouring mothers the care and tenderness they deserve.

This crisis isn’t just about the midwives. It’s about all mothers and families. As the celebrated American midwife Ina May Gaskin once wrote: “The way a culture treats women in birth is a good indicator of how well women and their contributions to society are valued and honoured.”

The Midwives who are pointing to the injustice of the current system remind me of Shiphrah and Puah. They’re the two Hebrew midwives in the Old Testament who refused the command from the King of Egypt to kill all male Jewish babies at birth.

The strength and courage of these biblical midwives prevented a genocide. But they also demonstrated a deep tenderness for the women they cared for, and their new babies.

When it came to it, they chose to give life rather than take it away.

So often the Christian tradition emphasises the stereotypically male attributes of God – of strength, victory in battle, and power. But there is also power to be felt in caring for another in the midst of labour pains; the light touch on the small of a back; the grip of a hand to help ease the agony of a contraction.

The God I believe in is like this. A God described in Psalm 71 as like a midwife: “he who took me from my mother’s womb”.

Like life itself, labour can be agonising. There are moments of unimaginable pain. But it can also at times be profoundly and eye-wateringly beautiful; and it’s good to have someone to hold our hand through it all.

BBC Radio 4: Thought for the Day - 10 August 2021

Good morning,

Over the weekend, I watched a terrifying video of a boat evacuating people fleeing wildfires in Greece. The boat was eerily moving out on the water as its passengers looked back at a landscape engulfed in flames. One evacuee on another BBC news clip in the Athens seaside suburb of Pefki described the situation there as ‘like a scene from an apocalyptic movie’.

Such visions frighten anyone with an imagination vivid enough to transfer the images to the bottom of their own street, as scenes of burning landscapes appear on our screens more and more often. What was once only the stuff of disaster movies and apocalyptic novels has become our reality.

Using the word Apocalypse to describe such moments points to the original theological sense of the word: an ‘unveiling’. In New Testament Greek, the book of Revelation is literally called the apocalypse of John. The word apocalypse here meaning revelation, that which is uncovered.

In yesterday’s IPCC report, a team of global experts sent a dire warning about the state of our planet; and told us the increased intensity and frequency of heatwaves, are unequivocally the fault of human actions.

The report was described as “a massive wake-up call” – a profound revelation in a sense, that we have got to drastically change course if we’re to have any hope of preserving the earth for future generations.

My climate anxiety feels at its most overwhelming when I think about the world my three-year-old son will be living in when he’s 33. But the revelation of the devastating reality of climate change requires us to have compassion not just for future generations, but for those today suffering its effects.

Christianity calls us to have compassion not just for our own flesh and blood, but the whole of humanity. There are people in some of the poorest communities today for whom climate change is not a debate, not a future revelation they might fear. They can see it right in front of their very eyes. And they too are our family.

The IPCC report sets out the actions we need to take. Scientists say a catastrophe can be avoided if the world acts fast to what the UN boss has called a “code red for humanity". Faith, too, compels believers towards hope. Hope that we’ll be able to work towards the common good. As the Pope wrote in his 2015 encyclical on Care for our Common Home Laudato Si : “Human beings… are… capable of rising above themselves, choosing again what is good, and making a new start.”

BBC Radio 4: Thought for the Day - 3 August 2021

Good morning,

The year was 2002 and the place was the London Arena. I’d joined thousands of other teenagers at the first Pop Idol tour, following the series that made household names of Will Young and Gareth Gates.

Pop Idol, and its successor The X Factor, promised to turn ordinary people into stars. In some cases stars were born. But now the X Factor has been axed. It’s gone from pulling in tens of millions of people each weekend, to dwindling audiences for whom the format has lost its shine.

Part of the appeal of programmes like The X Factor was a belief that people like us could have their 15 minutes in the spotlight and the fame, stardom, wealth and purpose that accompanied it.

But at what cost? Over the years we’ve seen the mental and physical toll that is placed on those who achieve stardom on reality TV, and this past week Simone Biles has powerfully reminded us of the pressure placed on Olympic athletes to achieve - and prove - their greatness.

I was recently captivated by Kazuo Ishiguro’s Klara and the Sun which has been longlisted for the Booker Prize. Told through the eyes of a robot designed to be an artificial friend to children, the story is a haunting narrative on loneliness, human relationships, power and the lengths people will go to achieve so-called success.

A theme that runs through it is the decisions parents in a not-so-distant-future must make about their children; whether to have them ‘lifted’ or genetically modified to enhance their performance and status – and risk their children’s health in the process.

In Ishiguro’s book, Klara, the artificial friend, wonders whether there’ll always be something within humans that remains beyond her reach no matter how hard she tries to understand and mimic them.

In Christian theology, that thing – that X Factor, if you will – is the imago dei, the idea that we are all made in God’s image and that a golden thread of the divine runs through every human, no matter their race, gender, sexuality, class - or singing ability.

We don’t need to prove ourselves as we are already something special in the eyes of God. The Christian idea of hope is grounded in that reality – which is not beyond our reach nor based on our abilities or efforts but offered freely.

Perhaps people loved the X Factor because somewhere beneath the bright lights and smoke, it spoke of hope. Maybe we’ll always need that in some form. Because, as Ishiguro writes about hope: [The] “Damn thing never leaves you alone.”

BBC Radio 4 Thought for the Day: 27 July 2021

Good morning,

I was delighted to see Team GB’s Olympic gold rush kicked off yesterday with swimmer Adam Peaty taking home the gold in the 100m breaststroke. He’s a master of the post-event interview too – paying tribute to his family who, he says, also own his victory, and speaking of his longing to hug his young son when he gets home….

I was also intrigued to hear about Peaty’s ultimate ambition – the aim to achieve what he describes as Project Immortal – a perfect, record-breaking performance, so good that it would be “almost inhuman and will never be beaten”.

This narrative of becoming super-human, of going beyond what is physically possible, of having your name etched somewhere in a sporting hall of fame, demonstrates something that is at its heart fundamentally human: our quest for value, recognition, and ultimately love.

But Peaty’s ambition aside - when transposed into society more widely this instinct can result in rampant individualism; a dog-eat-dog world where those with strength, power, and money are regarded and remembered while those who are poor, powerless and in any way dis-abled, are cast aside and forgotten.

The Hofstede framework – a study that’s been going for 50 years – ranks countries based on a number of different markers of culture. In it, the UK ranks highly on both individualism and what the study terms ‘masculinity’– a highly success-oriented and driven culture, despite the apparent contradiction with the British reputation for modesty and understatement.

Vertical societies are often capitalist; individuals compete with each other to be the top dog. While more horizontal societies think in terms of ‘we’ rather than ‘I’.

The sentiment behind the word ‘competition’ could be helpful here; rooted in the Latin word competere which is about striving together.

In competing we push each other to become ‘faster, higher’ stronger’ as we hear in the Olympic motto. I love that in the Olympics, nations do compete together – one person’s win belongs to the whole country.

Because the Bible is full of criticism of the individual drive for power and success and in fact flips success on its head with its promise that in the kingdom of God it’s the last who will be first. The symbol of Christianity – the cross and the crucifixion it represents – do not at first glance represent victory. In fact, they may seem like loss.

Perhaps there’s something we can all learn from how we deal with defeat. In the words of famous Christian missionary and Olympian Eric Liddell: "In the dust of defeat as well as the laurels of victory there is a glory to be found.”

It’s publication day!

It's publication day! We are finally here. And great news from my publishers - there's been such demand for the book that they are reprinting already!

I started writing this book before a global pandemic and George Floyd's murder, and the reckoning with racial justice that followed.

It is one of the hardest things I've ever done - writing a book through a pandemic alongside a full-time job, freelancing, starting a business and being a toddler mum! But it felt important. And like it was meant to happen at that exact time.

Thank you to all those who have supported me.

The book had been a long time in the making. I remember having a conversation with Katherine Venn at Hodder Faith a few years ago, in which the very first sparks of the book emerged. I’m really thankful to Katherine for her faith in me, the encouragement when I needed it, her patience, gentle nudges and challenges that made the book what it is.

I’m also hugely grateful for the expertise, passion and support of others at John Murray Press, including Rachael Duncan and Jessica Lacey. To those that took time out of their busy schedules to read the first drafts and gave me honest feedback and encouragement.

Thank you Jendella Benson, Dominique van Werkhoven, A. D. A France-Williams and Vicky Walker. Your insights made the book so much better than what it was.

Thank you to those who have been fighting this fight long before me: Professor Anthony G. Reddie, Archdeacon Rosemarie Mallett, Dr Elizabeth Henry and Professor Robert Beckford, whose wisdom also helped to shape this book. And, finally, none of this would have been possible without the support of my various ‘families’. My church family – the most wonderful community of people. My Christian Aid family – passionate and excellent human beings determined to make the world better. And my actual family. From mum and dad, who read various drafts and encouraged and corrected along the way, to my cheerleader sisters, to my husband Mark, who held me when I felt broken. And to my golden-brown boy, K, who had absolutely no idea what was going on, but whose cuteness was all I needed.

It's not an easy read, but I hope it will help bring change and remind us that all of us are made in the image of God.

I’m already blown away by seeing the number of people who have supported me by buying this book - from friends to family to strangers. I’m immensely grateful. (PS, don’t forget to post a review on Amazon!)

Thank you.

#GodIsNotAWhiteMan

BBC Radio 4: Thought for The Day - 25 May 2021

Transcript of my Thought for the Day on BBC Radio 4’s Today programme on the first anniversary of George Floyd’s murder. Listen to the audio here on BBC Sounds.

Today, people all over the world will engage in acts of remembrance to mark a year since the murder of George Floyd; lighting candles, saying prayers, kneeling and sitting in silence for the length of time in which Derek Chauvin knelt on his neck.

We know what happened next – the spread of the Black Lives Matter movement and a reckoning with racial justice across our institutions. I heard someone recently describe now dividing time between ‘before George Floyd’ and ‘after George Floyd’.

There was a sense – at least in the weeks that followed – that we could never be the same again.

Last week, I spoke at an event with Patrick Ngwolo – George Floyd’s pastor – and asked how he felt about the legacy of his friend’s death. He broke down as he remembered again the cruelty of watching Floyd’s execution – a prolonged and agonising death, while crying out for his mother.

Remembrance is important, but it can also be painful. Philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche wrote that life would be more joyful for all if we engaged in “active forgetting”.

It would be easy for me here to recast George Floyd as a Christ-like figure, whose death and sacrifice is ultimately for the good of us all. To show that black death demonstrates that where the world has been a place of injustice, oppression and violence for black people, there will be justice and peace in the world to come.

But why shouldn’t justice begin now? Why can’t there be life in all its fullness before death?

George Floyd was not a martyr who willingly laid down his life, but a victim of a pervasive system of oppression, centuries-long in the making, that sees black people as lesser.

Christians believe Christ died once and for all people. But black people have seen the brutalisation of the bodies of those who look like them time and time again. Today we remember George Floyd, but the annual calendar is marked with too many memorials to slain black men and women. We keep remembering. Because we have to.

Collective memory – memorials, statues, commemorations – help us make sense of today. We look back so we can move forward. The ritual of remembrance is an important space through which we can engage in transformation.

In the Last Supper, Jesus instructs his followers to continue to eat the bread and wine in remembrance of him. This act is not an empty gesture; but intended to be a place of remembering, before rebirth and then renewal. Through remembrance, transformation is possible. This transformation happens not in isolation, but in community.

As many light candles today to remember George Floyd, let’s remember to “fight racism with solidarity”.

From Lament to Action - Anti-Racism in the Church of England

I recently found a black and white photograph of my great grandfather, who was ordained an Anglican priest in 1940 in the south-east of Nigeria – a black man standing tall in his clerical garb.

I thought of him on Monday night as I watched the BBC Panorama programme Is the Church racist? which gave a damning account of individual encounters with racism and prejudice faced by black and minority ethnic clergy within the Church of England in the UK.

Some might wonder whether the Church’s institutional racism – as Archbishop of Canterbury Justin Welby described it last year - is just another step that feeds into a ‘woke’ agenda, the latest form of self-flagellation by social justice warriors.

But peering beneath the surface of the state Church and finding racism lurking beneath it is not new. It didn’t start with the Black Lives Matter movement.

The Church of England’s anti-racism taskforce has today published its report into institutional racism. As the House of Bishops said last year when the Commission was formed: “For the Church to be a credible voice in calling for change across the world, we must now ensure that apologies and lament are accompanied by swift actions leading to real change.”

But reports which show the biases that exist in institutions like the Church of England, again, are nothing new. The Church itself has produced scores of reports calling out the racism in its midst over the past few decades.

And yet here we are. In 2021. With black and brown clergy saying they feel excluded, discriminated against and made to feel less intelligent, less included, less worthy, less valued than their white counterparts.

This goes beyond political correctness, but cuts to the heart of the Christian gospel – the story at the crux of the faith that the Church of England professes.

A story that believes that all are made equal, created in the image of God, worthy of inherent dignity and respect.

It’s time for real, tangible changes to be made, as the anti-racism taskforce’s report From Lament to Action shows.

But in order to move forward, there has to be a facing up to the wrongs that have been done; there must be lament. But remaining in lament – saying sorry over and over again – can not in itself make the future better.

Confession is important – a facing up to sin. But even more importance is repentance. The Greek word metanoia translates as a transformative change of heart, an about face – a complete turning around.

There is something here we all can take from this – a collective recognition that things haven’t been as they should have been – whether in the church, other faith communities, or in our nation.

But change is always possible – change that is real and seen and felt.

As Martin Luther King Junior said, in speaking about the ‘fierce urgency of now’: “This is no time for apathy or complacency. This is a time for vigorous and positive action.”

—-

This blog is adapted from a script I had originally planned to deliver on BBC Radio 4’s Thought for the Day on 21 April, but following the verdict in the trial of Derek Chauvin, I presented this one instead.

BBC Radio 4: Thought for the Day - 21 April 2021

This is the transcript of the Thought for the Day I delivered on 21 April, the morning after the jury returned guilty verdicts in the trial of Derek Chauvin, convicted on all counts relating to George Floyd’s death. You can listen to the audio on BBC Sounds here.

Good morning,

“Let the people see what they did to my boy.” These were the words spoken by Mamie Till-Mobley – the mother of Emmett Till, after viewing the brutalized body of her teenaged son in 1955.

He was murdered – like many other black men and women have been for years and decades and centuries.

Mamie Till held a funeral with an open casket in the hopes that when the world saw – really saw - the violence committed against her son, that it would wake people out of the slumber of inaction on racial justice.

Last summer, the world saw police officer Derek Chauvin kneel on the neck of George Floyd – while he cried out for his mother - for 9 mins and 29 seconds, until he died.

His chilling words, ‘I can’t breathe,’ echoed the final words of Eric Garner in 2014 and Javier Ambler and Elijah McClain and Byron Williams, all of whom died of positional asphyxiation during their arrests between 2018 and 2020.

Yesterday we saw Chauvin convicted of his crimes; guilty of all charges over George Floyd’s death. Beyond a reasonable doubt.

When it comes to seeing guilty parties convicted, doubt has long existed among black communities – my community. We have seen generations of trauma, necks on the line, justice denied.

We know too many names of black people killed because their lives were viewed as lesser, resulting in a culture where even while jogging or waiting at a bus stop or going to the shops or even sleeping in their beds, black bodies are rendered at risk. The bodies of Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, Trayvon Martin and countless others in the US. Stephen Lawrence, Sean Rigg, Sheku Bayoh, Joy Gardner and many more in the UK.

And yet many black communities have kept the faith, even in the face of unimaginable horror and injustice, recognising in the biblical narrative a story of a God who sides with the oppressed rather than those who hold on to a power that corrupts.

Black theologian James Cone describes the gospel as “a story about God’s presence in Jesus’ solidarity with the oppressed... “What is redemptive,” he says, “is the faith that God snatches victory out of defeat, life out of death, and hope out of despair.”

While it will take more than one conviction to end injustice, we wait to see if this is the watershed moment, the turning point that has been longed for. But we can’t rest.

Because as – echoing the Old Testament prophet Amos - Martin Luther King said: “We are not satisfied and will not be satisfied until justice rolls down like rivers and righteousness like a mighty stream.”

—-

I write extensively about George Floyd and Black Death in my book God Is Not a White Man: And Other Revelations (Hodder & Stoughton, 27 May, 2021). You can order your copy here.

BBC Radio 4: Thought for the day - 13 April 2021

The following is a transcript, but you can listen to the BBC website here.

Good morning,

This week, many people will be celebrating a long-awaited trip to the hairdressers or barbers, or to have their nails done. Much more significantly - for some of them this may be their first physical human contact for over a year.

The coronavirus pandemic has starved many of physical touch. Although it’s also got rid of the awkwardness of having to decide how to greet someone: one kiss or two, a handshake or an embrace?

Nevertheless, many will be longing to sit in the hairdressers’ chair again, and feel the intimate and soothing familiarity of human contact.

As humans, physical contact isn’t just a nice-to-have. It’s a necessity; a need that is vital at key moments in our lives – from birth to death.

I was moved to tears when I saw on social media a photo depicting a harrowing yet beautiful image. Nurses in a Brazilian covid isolation ward had created what has been described as ‘the hand of God’ – two disposable gloves tied, full of hot water, simulating human contact, to bring comfort to patients separated from their family members in their final hours of life.

There is something disturbing about the image – how can a warm rubber glove take the place of a loved one’s hand as someone takes their final breaths? But it certainly reminds us of how important it is for us to be touched, held, embraced – especially in our darkest moments.

The rubber-gloved hand of God reminds us of what has been taken from us during this pandemic.

Many scientific experiments have been done which demonstrate the importance of human touch to child development. Children in Romanian orphanages in the 1980s grew up with physical and mental delay in part due to the lack of basic human touch they received, while 13th century historian Salimbene described the tragic consequences of an experiment on babies in isolation, which led to many of them dying. “They could not live without the caresses,” he said.

I myself remember the agony of not being able to hold my baby boy for hours on end as he received treatment during his first few days of life.

At the heart of the Christian story is this idea that God moves from the ethereal and immaterial, to the physical. The incarnation – God becoming human just like us in the form of Christ – is able to touch and to be touched. He is not a disembodied ghost.

The gospel accounts show Jesus’s willingness to bring healing, comfort and acceptance through touch: embracing a man with leprosy, long shunned by the rest of society; touching the eyes of the blind and bringing sight.

God is with us in the incarnation, in the magic of a hairdressers’ fingers and the beautifying touch of a manicurist’s hand. As Michaelangelo said: “To touch can be to give life.”

Thought for the day - 31 December 2020

I was honoured to present the last Thought for the Day of 2020 on BBC Radio 4’s Today programme, guest edited by Bishop Rose Hudson-Wilkin

Good morning,

Last year, I joined family members from all over the world for my grandmother’s funeral in Nigeria. As is tradition, we took part in three days of mourning – a night vigil in the darkness of the grounds of my family’s ancestral home, a burial service attended by a thousand people joining our family at our time of mourning.

The third day involved a church service where we combined giving thanks for my grandmother’s life with giving thanks for the new life we now had, through the birth of my son, who hadn’t yet turned two. This was the first time the whole family had been together to welcome him, the first grandchild.

And so it was that my husband and I found ourselves dancing up the aisle holding our son aloft with around 50 relatives, plus goats, yams and wads full of cash. I found it incredibly moving - overwhelmed by the love for us as a couple and for our son; in my culture when one of us is blessed, the whole community receives the blessing.

In that moment, I understood something of the African proverb that says it takes a village to raise a child. Our little boy didn’t just belong to us, he belonged to all of us.

To me, in this strange year, I’ve been reminded of the profound concept of Ubuntu. Our health, our happiness and our flourishing, are infinitely bound up with the flourishing of our communities.

I’ve seen glimpses of it this year, in the strength I’ve found in solidarity with my neighbours, in small acts of kindness, in people staying at home to protect strangers, in the empathy with those who have faced unimaginable loss. Lost livelihoods, and lost lives. Fear, anxiety and heartbreak.

Many of us will be relieved to see the back of 2020. But as we step into 2021, with all the hope and expectation of a new year intensified by the fact that over the past 12 months, we have lived through a kind of collective trauma, my prayer is that we’ll live by the concept of Ubuntu, of togetherness. As a Christian, I believe the thing that binds us together is being made in the image and likeness of God.

Who knows what 2021 will hold? But I’m clinging to hope, whatever happens. Choosing togetherness, and - in the words of St Paul – to rejoice with those who rejoice and weep with those who weep. Just like my family gathered in Nigeria to mourn death, and celebrate life.

Former US president Bill Clinton put it well when he said Ubuntu “means that the world is too small, our wisdom too limited, our time here too short, to waste any more of it in winning fleeting victories at other people’s expense. We have to now find a way to triumph together”.

BBC Radio 4: Thought for the day - 4 December 2020

It all begins with an idea.

In a remarkable interview on this programme yesterday, artist Tracey Emin spoke of her harrowing experience facing death after being diagnosed with bladder cancer in June.

Within weeks she underwent major surgery that removed several of her organs.

“They’re calling me miracle woman,” she said, relaying how she thought she might not even make it to Christmas and the overwhelming sense of relief that came with her miraculous recovery.

When you come face to face with your own mortality and then in a sense get a reprieve, you’ll never take anything for granted again and you will try to do your best in life, Emin said.

As a person of faith, I heard in her voice an unbridled sense of joy and of relief, and found resonance in the words she used with, for me, a theological understanding of grace, renewal and rebirth. “I feel like I’ve been forgiven, or like a big giant curse has been lifted off me,” she said. “I feel like this is the real, true beginning.”

You could say it’s like she’s been born again.

I believe the post-Covid world presents us as a nation with an opportunity to be born again, too, like Ebenezer Scrooge who wakes up on Christmas morning a transformed man wanting to do good in the world.

Some of us have already seen signs of this rebirth in lessons that 2020 has taught us about whose lives matter,

the importance of connection at a community level, the appreciation of nature,

the spotlight on UK poverty, the vital importance of our key workers and the questioning of whether we’ve got the balance of work and life right thus far.

We are at what economists Daron Acemogly and James Robinson described as a ‘critical juncture’ – a sudden and unforeseeable jump such as a war or a pandemic that disrupts the status quo, the existing balance of political and economic power.

A critical juncture provides a crossroads at which there is an opportunity for real change, for rebirth.

But what could this re-birth look like for us as a nation? In the months ahead as we begin to emerge from the ruins of this year, having collectively come face to face with our own mortality, what will we take with us into this new world?

My hope is that we will be born again into it; but that each of us must recognise the part we play in making it a reality. I hope we’ll become kinder, more generous, more aware of the needs of those around us. I hope we’ll never take anything for granted again.

Because perhaps, as in the words of Tracy Emin, we’re on the cusp of something and there’s no more messing around.